Abdinasir Abdi: Helping improve education standards in Somalia

Most graduates in business tend to choose a career involving accounts, finance and marketing, to name but a few. Not so for Abdinasir Muhumed Abdi.

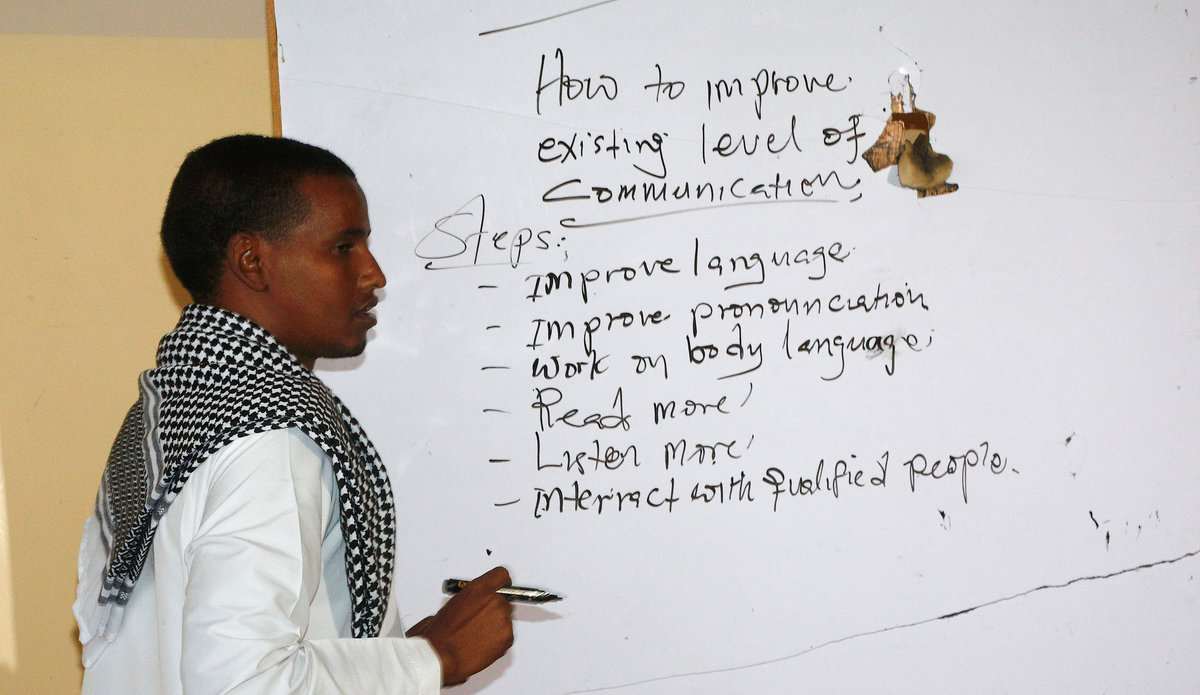

Despite finishing university with a degree in business administration, the 33-year old decided that his calling lay with educating college students in the subjects of English, communication skills, social studies and public administration among others.

He credits an uncle of his, one to whom he was very close, for convincing him to pursue teaching, not only as a career but also as a service to Somalia.

“I used to sit next to him as he marked students’ assignments and he would tell me interesting stories about the profession and why I should pursue it,” Abdinasir says.

“He made me view teachers as problem-solvers; the people society look up to for solutions,” he adds.

Abdinasir was born and raised in Belet Weyne, the capital of Hiran province in south-central Somalia, a few years before the outbreak of the civil war in 1991, which led to the collapse of the central government, leaving the education sector, which heavily depended on state funding, in disarray.

Even then, education – his own, in this instance – was important to him. He often had to dodge bullets to reach the few schools that were still operational.

“It was difficult going to school in an environment where conflict was the order of the day. However, I was determined to complete my primary and secondary education,” Abdinasir says, noting that many of his classmates were not as determined and ended up fleeing the country or joining militia groups controlled by warlords.

Finishing his primary and secondary studies, he moved in 2008 to the national capital, Mogadishu, where he enrolled at Simad University for his undergraduate studies.

Caught in a crossfire

However, the violence he had experienced attending school in his home town was also part of life there, with his arrival coinciding with fierce fighting for control of the city.

He still remembers an incident, not long after arriving, involving militants from the Islamic Courts Union and Ethiopian troops, who had been deployed to Somalia to support to the Somali Transitional Federal Government which was under threat by warlords.

“That day I was heading to the university. I boarded a public transport vehicle from a nearby bus stop. A few minutes later, armed men suspected of being fighters loyal to Islamic Courts Union, which had been pushed out of the city, launched an attack on the nearby Ethiopian military base nearby. The Ethiopians began firing back using heavy weapons and we were caught in the crossfire that lasted for an hour,” he remembers.

“One of the passengers in the vehicle was killed and eight others sustained serious injuries,” he notes. “It was Allah’s miracle that I managed to survive to pursue my education.”

Daily violence was only one part of the challenges he faced. Some months after that particular incident, Abdinasir experienced serious financial problems, leading him to take on a part-time teaching job to make ends meet and ensure he could afford to continue his studies.

There was also another motive at play.

“Apart from making some money for my basic needs and also paying school fees, I wanted to help the children, who were already traumatized by the war, acquire education since most of the teachers in Mogadishu had fled,” he explains.

Returning home

Upon completing his university education in 2013, Abdinasir returned to Belet Weyne, with the desire to continue teaching and to help improve education standards in his home region, which had been ravaged by conflict.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), Somalia has one of the world’s lowest enrolment rates for school-aged children. UNESCO estimates there are currently some 4.4 million out-of-school children, almost half of the country’s total of 9.2 million people. In terms of proportion, only four out of 10 children are in school.

Recently, Somali educational authorities launched a new unified and streamlined education system for primary and secondary schools across the country, ensuring one coherent and cohesive structure for all students, no matter their location.

Abdinasir has high hopes for it being able to improve enrolment rates in the country.

“If the programme is well managed, it will end the confusion brought about by the different syllabuses taught in schools and give our children a fresh start towards acquiring quality education,” he says, adding that he believes a pre-civil war government policy of free and compulsory education should also be returned.

As the world marks International Literacy Day – observed annually on 8 September and seen as an opportunity to highlight improvements in world literacy rates, and reflect on the world's remaining literacy challenges – Abdinasir expresses the hope that his views on Somalia’s educational needs are shared more widely, for the sake of the country and its future.

“If Somalia is to have a highly skilled and educated labour force, then parents should start taking their children’s education seriously or else the country will continue lagging behind,” the 33-year-old observes.

UN

UN